The Egawa Albion

River and Streams

The Story of the Iron Press at Manoa

It was Rupert Tevis, an old friend, who first showed me the iron handpress in the art room at Windward Community College above Pearl Harbor. The press was an albion, painted black. In relief on the cap: 江川: rivers and streams. On the back: a rising sun. I pulled the bar. The press wobbled and shook, but it worked.

I got Rupert to find out if the college would sell me the press.

“No,” I was told. “Only the owner can sell it, and no one knows who that is.”

Disappointed, but determined to get Mānoa Press up and running, I built my own press; but within a few years I had entirely outgrown it.

One day, exasperated with the press I had made, I drove out to the college, determined to get my hands on that albion. I flung open the door to the art room. The press was gone!

I accosted the teacher. “Where’s the press?

The students turned around.

“You mean that old one? It’s been taken over to the theater,” the teacher said.

At the theater, a stagehand remembered the press, hidden behind a rack of costumes.

“Can I buy it?” I asked.

“Probably, if the owner can be found. Give us a month.”

A month later, still no owner; but the theater thought that if I made a donation of $250 to the college, I could have the press. I was elated. I wrote out the check, and the stagehand helped me take the press downstairs. My wife went to get the car. She left me standing atop a grassy hill. I took in the expanse of Pearl Harbor. A real press at last!

Then a lone figure, hidden against the setting sun, crossed the field.

“Hey! Where are you going with my press?”

Impossible. Not now. Not the owner.

“I just bought this press,” I said.

The man, a professor at the college, explained that he was not the real owner, just its caretaker. The reputed owner was a Dutchman named van Kralingen, whom he hadn’t seen in twenty years. When we failed to locate van Kralingen in the phone book, the professor said,”Well, you might as well take it. You know, this press was in the movie “Hawaii,” and on a “Magnum PI” episode. Don’t know where the press came from though.”

My wife and I drove home and waited until dark before unloading the car. What if van Kralingen should drive down the road?

The next day and for the next several weeks, I busied myself, repairing the press: new tympan paper, a new brass frisket, nylon rounce straps to replace the rotten leather ones, and a professional regrinding of the platen and the bed. Here and there, the black paint had chipped off, revealing a layer of mustard yellow—clues to its past.

I rented the movie “Hawaii,” and there was my press. The rising sun and the Chinese characters were covered over with black paper. Max von Sydow and Julie Andrews hovered lovingly over an iron press that could never have served the missionaries. The albion was first made in England in 1822. In that same year, half a world away, the missionaries were already at work, printing on a broken-down Ramage. Hollywood history. Was it Hollywood that had painted the press black?

Or was it van Kralingen? Few remembered the man. He had helped a local museum set up a period printing office in the late sixties. He had been active in unionizing the newspaper workers. He was known to be opinionated, if not quick tempered. Where he was in 1992, no one knew.

And before van Kralingen?

In his book on printing presses, James Moran mentioned the existence of a Japanese albion in Singapore. The press looked like mine, except for the absence of the rising sun and the Chinese characters. Moran tells us nothing about who made the press or when.

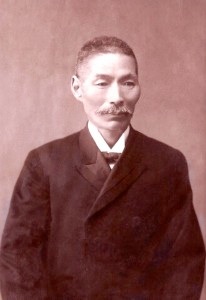

As for the characters on my press, to a Japanese they mean ‘bays and river’ and signify the family name Egawa. History books on Japan usually list only one Egawa: Egawa Tanan 江川旦庵 (1801-1855), maker of the country’s first blast furnaces. I wrote letters to the biographer of Egawa Tanan and to a professor of Japanese technological history. Egawa Tanan had never made printing presses. My correspondents suggested that I try the printing Library in Tokyo known simply as “The Printing Library” 印刷图书馆.

As it happened, I was going to Japan that summer to study paper making.

Tokyo in summer is a hot miserable place. Even at ten in the morning I was sweating as I ascended the elevator to the library.

“Hello,” I said to the librarian.

She flushed. She knew no English.

I scribbled in telegraphic Chinese (I know no Japanese):

江川日本印刷机制造十九世纪:

Egawa · Japanese · press · make · 19th century

She bowed and began punching numbers on her phone.

“Choto mate,” she smiled.

Not long after, the fax machine whirred and spit out pages of information sent from all over Tokyo. The name Egawa appeared here and there. My eyes jumped from page to page trying to glean the sense of the Chinese characters from the incomprehensible-to-me Japanese.

The phone rang. The librarian handed me the receiver.

“Hello?” I said.

“You come my office now. Yes? Librarian will show you. Good bye.”

I turned to the librarian, who was already writing out the address in English letters and drawing me a map to the Mizuno Printing Company.

It didn’t take me long to get lost. The building 2-9-2 Irifune had obviously evaporated in the heat. Then I remembered Irifune’s, a Japanese restaurant in Honolulu, and formed the Chinese characters in my mind: 入船.

I looked up and spotted the street. “Irifune, enter-the-boat,” the sign said. I smiled. I liked the metaphor. I would take the boat to cross egawa, the bay to the river.

At 2-9--2, in big red letters: MIZUNO. Under it, the characters for ‘wetlands’ 水野. Auspicious.

Inside the building, a receptionist offered me cool, crimson-colored slippers for my sweaty feet. When Mr. Mizuno, the owner, entered, I gave him my business card and bowed awkwardly. “Please come up to my office,” he said smiling.

Mr. Mizuno’s office was sumptuous. We chatted; then he led me to the elevator.

When the elevator doors opened, I saw a room filled with restored antique iron presses, shelves lined with books, and here and there displays explaining the evolution of writing and printing. “My museum,” Mr. Mizuno said.

My eyes gleamed.

Mr. Mizuno showed me a Buddhist sutra, which the Empress Shotoko ordered printed in 764.

“This is what first got me interested in the history of printing,” Mr. Mizuno said. “My father started this company and when I was a young man, he sent me to Germany to study. Why? Because printing had started there. But one day, I learned that the oldest printed things in existence were these sutra done by my countrymen. I felt ashamed. I was unaware of the contributions my own country had made. I returned to Japan after my studies and decided to find out all I could about Japanese printing. This museum is the result.”

We looked at early Chinese printed books. Mr. Mizuno opened up the cases. He let me touch the pages printed by Gutenberg and run my hand over the blocks of cherrywood carved in Japanese.

Mr. Mizuno then turned my attention to the large Stanhope press, which looked oddly like a squatting sumo wrestler. A Stanhope like this had been brought to Nagasaki by the Dutch in 1850. In 1858 the Japanese used it to print the first western-style books and newspapers.

Mr. Mizuno showed me his Columbians and Albions. After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, presses like these poured into Japan and fueled the march toward progress.

But Japan had no intention of relying on foreign made machines. Mr. Mizuno pointed to a cast iron albion made in Japan by a Hirano Tomiji 平野富二 (1846-1892), a native of Nagasaki.

But this was like my press! Hirano must have known Egawa! I had to calm down.

Hirano, it turned out, was a disciple of the great Motoki Shozo 本木昌造 (1824-1872), an official interpreter of Dutch and English in Nagasaki. Motoki had, among many things, been very interested in western printing techniques. In 1848, he had bought a Dutch-made press and types. In the 1850s, while under house arrest for speaking his own mind, he made plans as to how he would use his press to print Japanese language books. But when Motoki was made an interpreter for a Dutch shipping expert, his insatiable curiosity turned from printing to iron-shipbuilding.

It was at this point that Motoki noticed a sixteen-year-old named Hirano. He took the boy under his wing. When the two were caught in a typhoon and stranded on an island for five months, a special bond developed between them and they remained close friends for the rest of their lives.

Back in Nagasaki, the two continued to work together until Motoki, as independent and openly critical of the bureaucracy as ever, left shipbuilding and set up a western-style school.

Motoki could have picked no better time. Within a year, the Meiji era of “bright rule” was established. Japan was headed for full-scale modernization.

Motoki’s idea was to cast Japanese types so that he could print books for his students, but, immediately, he ran into trouble. Motoki’s craftsmen found it difficult if not impossible to make the matrices or moulds to cast the type. As Motoki was a Christian, he got in touch with a William Gamble, head of the Protestant mission press in Shanghai. Gamble had figured out a way to make matrices by electrodeposition and came to Japan to share his discovery.

What Gamble did for Chinese, Motoki soon accomplished for Japanese. Within two years, he had printed his first book.

Mr. Mizuno showed me Motoki’s first efforts. The progress in a few short years was astounding.

Motoki than began to expand his business rapidly. He set up a type foundry in Tokyo in the district of Tsukiji, not far from where Mr. Mizuno and I stood.

Then things began to fall apart. Motoki, as farsighted as he was, was no business man. He appealed to his one-time student for help, the brilliant Hirano, for how else to describe a man, who at the age of twenty-three was the president of Kosuge Shipyard in Nagasaki, the very shipyard that would eventually become Mitsubishi? Hirano resigned his position immediately, and went to Tokyo—to his old comrade and teacher.

Together they put the business back on solid ground. Then, in 1872, Motoki died and Hirano, grief stricken, took control of the business. The first thing Hirano did was to acquire more land in Tsukiji. He built a type foundry and a machine works. Within the year, with the help of machinists like Nakajima Ikusaburo 钟岛几三郎 and Motobayashi Isakichi 本林勇吉, Hirano was producing his own printing equipment.

The press before us was one of Hirano’s and company’s first efforts, for at the top of each post was a capital H. Mr. Mizuno’s press, however, was missing its tympan and frisket as well as its corner irons. “This press has been through a lot,” Mr. Mizuno said.

I told Mr. Mizuno about my press, but he had never heard of Egawa. Small wonder. All trace of Egawa’s efforts had probably been obliterated durning the war, when the militarists grew insatiable and melted down Meiji-era Japan, turning into canons the civilizing machines made by people like Motoki and Hirano, even Egawa.

Before I left, Mr. Mizuno presented me with a copy of a book on his museum. He inscribed it in Japanese with the words: “Where printing exists, there exists civilization.”

I went back out into the summer heat. I was starving. On the main street, I stopped at what I would call a lunch-shed: awning, counter, and a display case of tempting plastic reproductions of the specialities. I pointed to what I wanted. The lanky cook was amused. His wife chided him about something as he broke two eggs for my omelette-topped rice.

Motoki, Hirano, Egawa. They or their workers had walked here. Perhaps they had had a similar dish on a similar hot day. Unlike the ukiyo-e depictions of bustling Meiji Tokyo, these Heisei streets seemed deserted. The reminders of the past were gone. Only the Mizuno Museum down the street and the Printing Library nearby were keeping the memories alive.

I pulled out the thermal fax and unrolled it like a precious scroll. I began a slow and painful winnowing, separating the Chinese characters from the incomprehensible chaff:

Egawa born the fourth year of Prosperous Eternity, pedlar, brilliant businessman, contracts, presses, tarnished reputation died the forty-fifth year of Bright Rule.

It was too much for me now. I rolled the fax back up and headed for the subway.

In the intervening years since 1993, I made several attempts to have the information I gathered that day translated but I became too busy with other things. In 2001, I decided that the time had come. I opened the folder on Egawa. The thermal fax had faded to almost nothing. Unperturbed, I photocopied the nearly blank pages. With the right adjustments, the story of Egawa flickered back to life.

Egawa Tsuginoshin 江川次之進 was born in 1851 in the small village of Higashiju, Sakai, Fukui. At thirty-one years of age, he went to Tokyo. He drifted from menial job to menial job. One such job was peddling type for a Mr. Yamaguchi. It wasn’t long before Egawa thought of a way to improve business. He showed his clients how to use the type and give their small establishments the look of modernity.

Business took off. Egawa bypassed Yamaguchi and dealt directly with the Tsukiji Type Foundry, developed by Motoki and Hirano. When the Tsukiji foundry couldn’t meet his continual demand, Egawa established his own foundry and, unlike other foundries, hired workers at decent wages.

In the late 1880s, Egawa decided to design a new typeface, modeled on a cursive style of Chinese writing called gyosho 行书. But cutting the alternating thick and thin lines proved nearly impossible. After much trial and error and thousands of yen, Egawa succeeded in producing gyosho and in 1889 made several sizes available. Egawa’s triumph was celebrated for many years, and now the name Egawa is the name of a digital Japanese-language typeface or font.

Next, Egawa decided to sell presses made by Nakajima Ikusaburo of Osaka. Nakajima, it may be remembered, was one of those who worked on the Hirano press in the early 1870s. Then at the turn of the century, Egawa, at the peak of his business prowess, took on Motobayashi Isakichi, another press maker from the Hirano days. In 1899 and in 1900, Motobayashi made printing presses for Egawa.

At about this time, Motobayashi began making bad business deals and dragging Egawa’s good name through the mud. Fortunately, the printing community rallied behind Egawa, and Egawa’s reputation was restored. Egawa died soon after in 1912, the last year of the Meiji reign.

Unfortunately, Egawa’s unknown biographer, writing in 1934, never mentioned the kinds of presses Egawa made nor when he made my albion. Even so, I would like to think that 120 years ago, my press lay cooling in its sand mould, waiting to be drilled and filed, given a coat of black lacquer and sent off into the world.

My press must have been born under a lucky star. It had come to Hawai‘i long ago and had escaped the fires of war. In 1905, there were two or three Japanese language printers in the Hawaiian Islands. Perhaps one of these men used an Egawa-made albion as a proof press. For now, no one knows or remembers.

For almost thirty years, the Egawa albion, the press I still think of as “Rivers and Streams” has been at Mānoa Press.

About ten years ago, a friend named Jack Reisland and I restored the press. Through his guidance and expertise, we stripped the black paint from the press and removed the undercoat of yellow primer. We filed and scoured off places that had been badly damaged by rust. Then Jack nickel-plated some of the parts. We gave the rest of the press a good coat of black paint. Then carefully, Jack painted the rising sun a dazzling red and Egawa’s name shining gold. And when all was done and all the parts were reassembled, he made a wooden base for the press. On the base he carved 江川—rivers and streams.

My thanks to the late Harue Summersgill, retired professor of Japanese, who helped me understand the various Japanese articles I brought back in 1993, especially the unsigned biography “Egawa Tsuginoshin, Gyoshotai Katsuji no Soseisha” in Honpo Kappan-kaitakasha no Kushin, (Tokyo: Sanshodo, 1934, 176-183)