The Chinese Giraffe

麒 麟

This is the author's edition, published by Manoa Press in paperback.

To purchase a copy of Chee-Lin, the Story of a Giraffe, click here.

Not much is known about the Chinese explorations of the early fifteenth century, years before Columbus. Only a few records remain. The rest is speculation. Of the remaining records, there is recorded the arrival in China, at the Ming court, of a giraffe born in the grasslands of East Africa.

When I discovered this bit of information, my imagination got the best of me and I wrote down a story of the giraffe that was taken to China.

Odds and Ends about Writing Chee-lin.

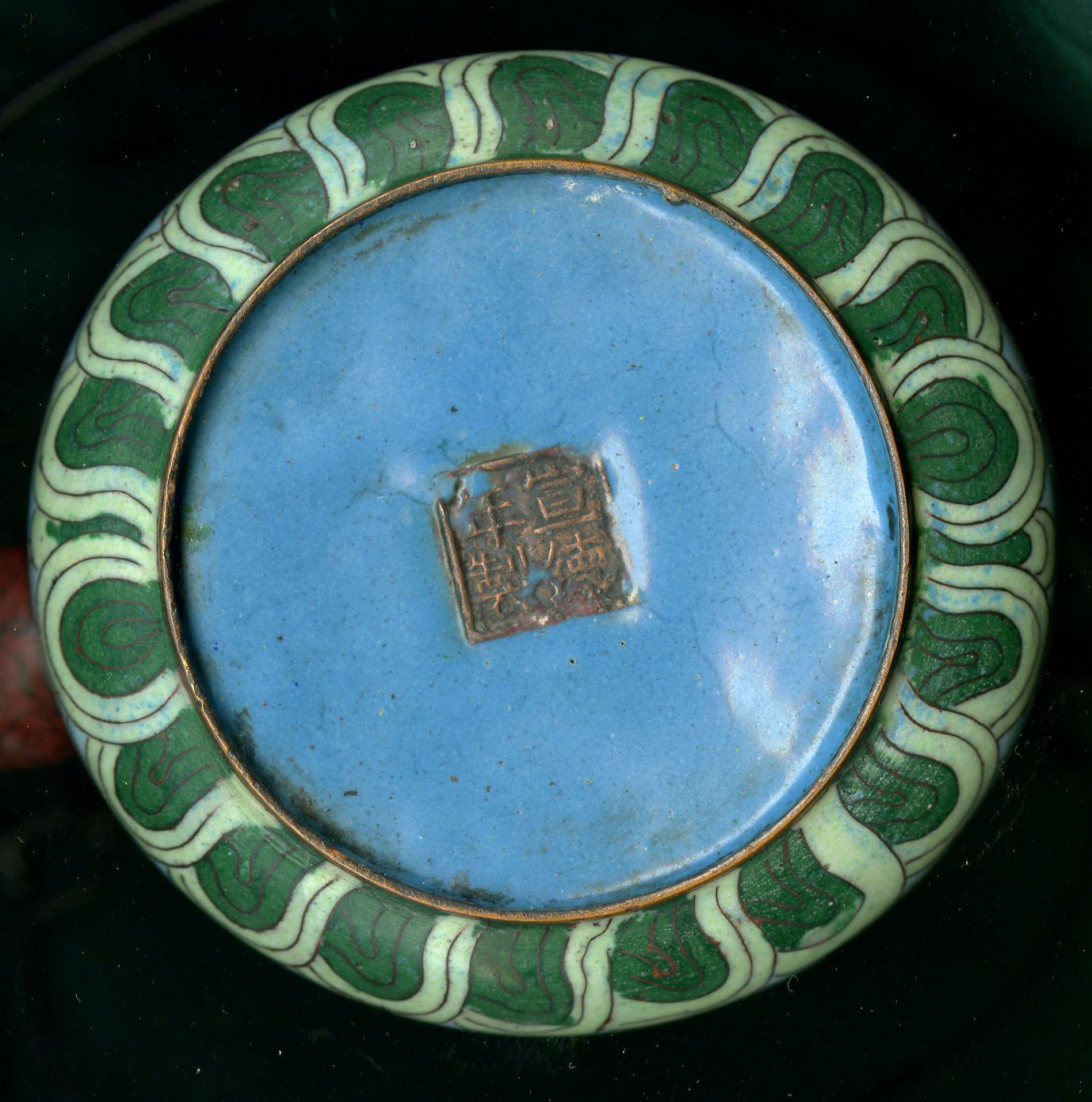

The Teapot: As I was writing and illustrating this book, I would search the internet for images of chee-lins. On e-bay, I found an old cloisonné teapot from China. On it was an image of the chee-lin, which I have outlined here in pen.

The teapot was dated with the emperor’s name on the bottom:

It read : 宣德年製 :: Made in the year of Xuan-De.

Xuan-De (宣德, 1399-1435) was emperor of China for ten years between 1425 and 1435. That meant that this cloisonné teapot was, if real, quite old and was made when my story took place. What was more, it only cost me one dollar! Okay, so the shipping was $80 from Beijing, but the teapot did arrive in two days as promised by the eighteen-year old seller, who for a while carried on a lively correspondence with me in Chinese. I’m not sure that the teapot is really from the fifteenth century, although the style of cloisonné seems to suggest such an early date. I decided to put the teapot in one of my illustrations for Chee-lin. In this painting you can see the teapot and an old Chinese brass tray of my grandmother’s.

On the following page you can see Xuan-De’s son Zheng-Tong (正統 1427-1464), who ascended the throne in 1435, when he was seven years old. (I drew him as a nine-year-old.)

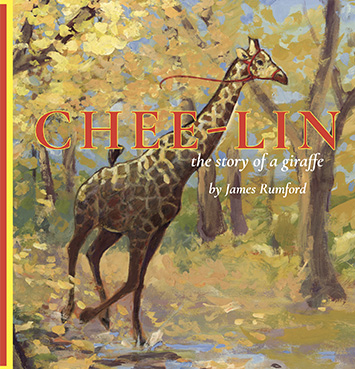

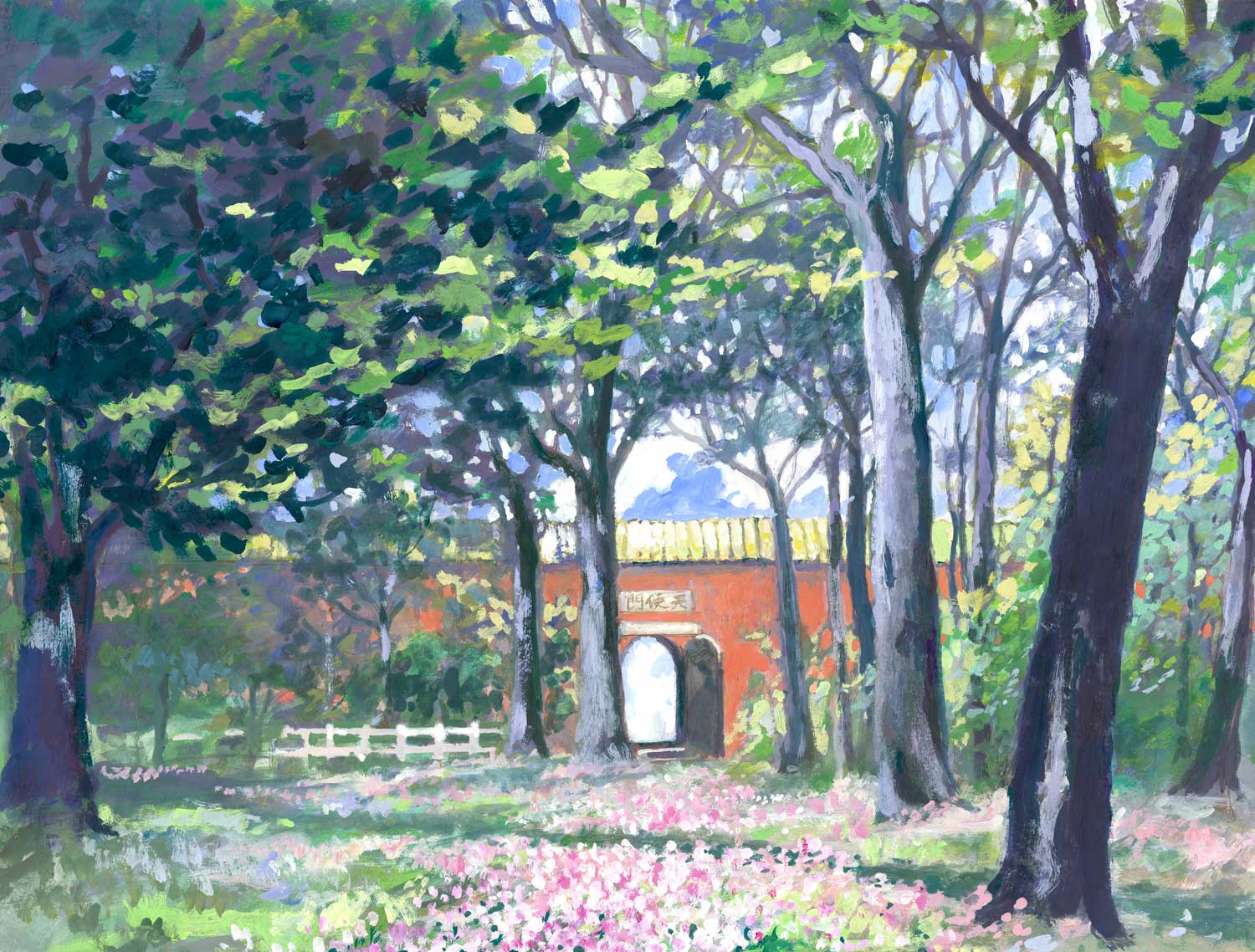

The Illustrations: People often ask me what is my favorite among the books I have written. I say, “I don’t know. It is kinda like asking a parent which is his or her favorite child.” But if someone were to ask me which illustrations were my favorite, I would have to say these that I did for Chee-lin. Like the watercolors I did for Dog-of-the-Sea-Waves, these illustrations have largely gone unnoticed. They are old-fashioned; they do not sing with the times. Be that as it may, I really enjoyed doing these illustrations for Chee-lin. I used a new medium—to me—casein, which is pigment mixed with essentially milk. Casein is ancient. Cavemen knew the properties of milk, which, when dried, stuck pigment to cave walls. Unlike oil paint, however, casein has one annoying property: it dries quickly. Fortunately, though, I live in Hawai‘i, where it is humid. The humidity greatly slowed the drying time. Another enjoyable aspect of doing these illustrations was the fact that I did them in the style of French impressionist painters, whom I have always admired. This particular painting by Monet, called “The Bodmer Oak,” painted in 1865, was the inspiration for the last painting in the book:

But the best part of doing these illustrations in the impressionist style was this: I was so into it that everything I looked at I turned into an impressionist painting: the trees and the dappled light on the street, the plumeria tree in flower in front of my house, the white waves crashing on the distant reef, disturbing the perfect turquoise color of the ocean. Sadly, this way of looking at my surroundings ended the day I finished the last illustration.

From My Notebooks: Here are some pages from my notebooks. This is a sketch of Chattering Man that never made it into the book:

These are sketches of Whispering Girl:

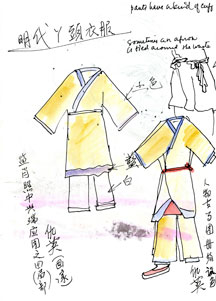

I was particularly interested in what servants in the imperial household wore. I looked at lots of paintings and took notes:

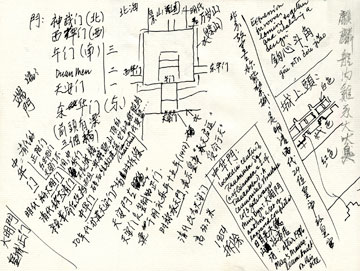

I also needed to know what the Forbidden City in Beijing looked like and the one in Nanjing. The one in Nanjing, though grander than the one in Beijing, had been destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion in the middle of the nineteenth century; so there were no photos and very few paintings. Thus, I had to make a lot of guesses for the painting I did of the emperor viewing the Chee-Lin. Here are some notes I made from looking at Chinese books: