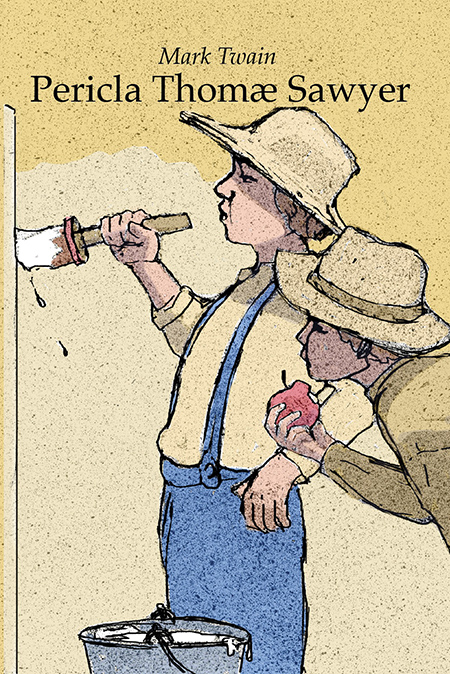

An American Classic in Latin,

completely revised with macrons added.

To purchase a copy of Pericla Thomae Sawyer, click here.

Because some earlier editions (before June 2021) had serious errors, contact me about how to obtain a revised pdf of the book.

IT HAS BEEN MY PLEASURE to get to know Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer under the microscope of translation. Let me add my bit of praise to all the accolades this book has received since it was first published in 1875. Not only is Mark Twain a consummate storyteller but he is a master of giving voice to the people of the village of St. Petersburg, of allowing the reader to enter their lives and feel what it was like to live along the banks of the Mississippi in the mid nineteenth century.

As a translator I have had to find appropriate ways to turn what I might call his exuberance of language into Latin, to come to terms with his run-on sentences, his long paragraphs knitted together with commas and semicolons and dashes. Equally daunting were his colloquialisms, some of which have faded—even for me a native speaker of American English—in meaning over the many years since the book was published. Fortunately there was help: many scholars of Mark Twain have added their comments about the most difficult expressions and there was a German translation done by Morik Busch in 1876, which clarified many difficult passages.

In translating this book, I have relied heavily on the books translated by Arcadius Avellanus [Mogyorossy Arkád], perhaps the last native speaker of Latin. Avellanus [1851–1935] was born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and learned Latin before he was fluent in his native Hungarian. He later came to America and was a proponent of living Latin.

I used the internet and the digitized books he translated as a “living” dictionary, locating the words and expressions I needed in English and finding Avellanus’ equivalents in his Latin translations. Always, his translations were lively and gave me the feel that they were done by someone who knew Latin to the very core of his being.

Besides Avellanus’ books, I also looked at many other works translated by Latin scholars and teachers. Among these I might mention the translations done by Clive Harcourt Carruthers [Alicia in Terra Mirabili, St Martin’s Press, 1964, and Aliciae per Speculum Transitus, St Martin’s Press, 1961] and by Antonio Peral Torres [Dominus Quixotus a Manica, Centro de Estudios Cervantinos, 1998].

This second edition of the book was undertaken in 2021 not only to correct many egregious errors but also to indicate vowel length by adding macrons. This last I felt was necessary for those beginning to read Latin, for macrons help not only with pronunciation but also with decoding the meaning. Unfortunately, not all scholars agree on the placement of macrons; so in some instances I simply made a choice, deferring most often to the Oxford Latin Dictionary (2012) and in a few rare cases, as in scientific Latin or newly-coined words, I left the word “unmacronized.”

Most of the names of the characters are easily recognizable; a few are not. Aunt Polly has become Matertera Maria, since Polly ultimately derives from Mary. Sid has become its “ancestor” Dionysus and Huckleberry has become Vaccinius, derived from vaccinium, the Latin name for bilberry or American huckleberry.