There are no real endings—

just the mystery of what is to come.

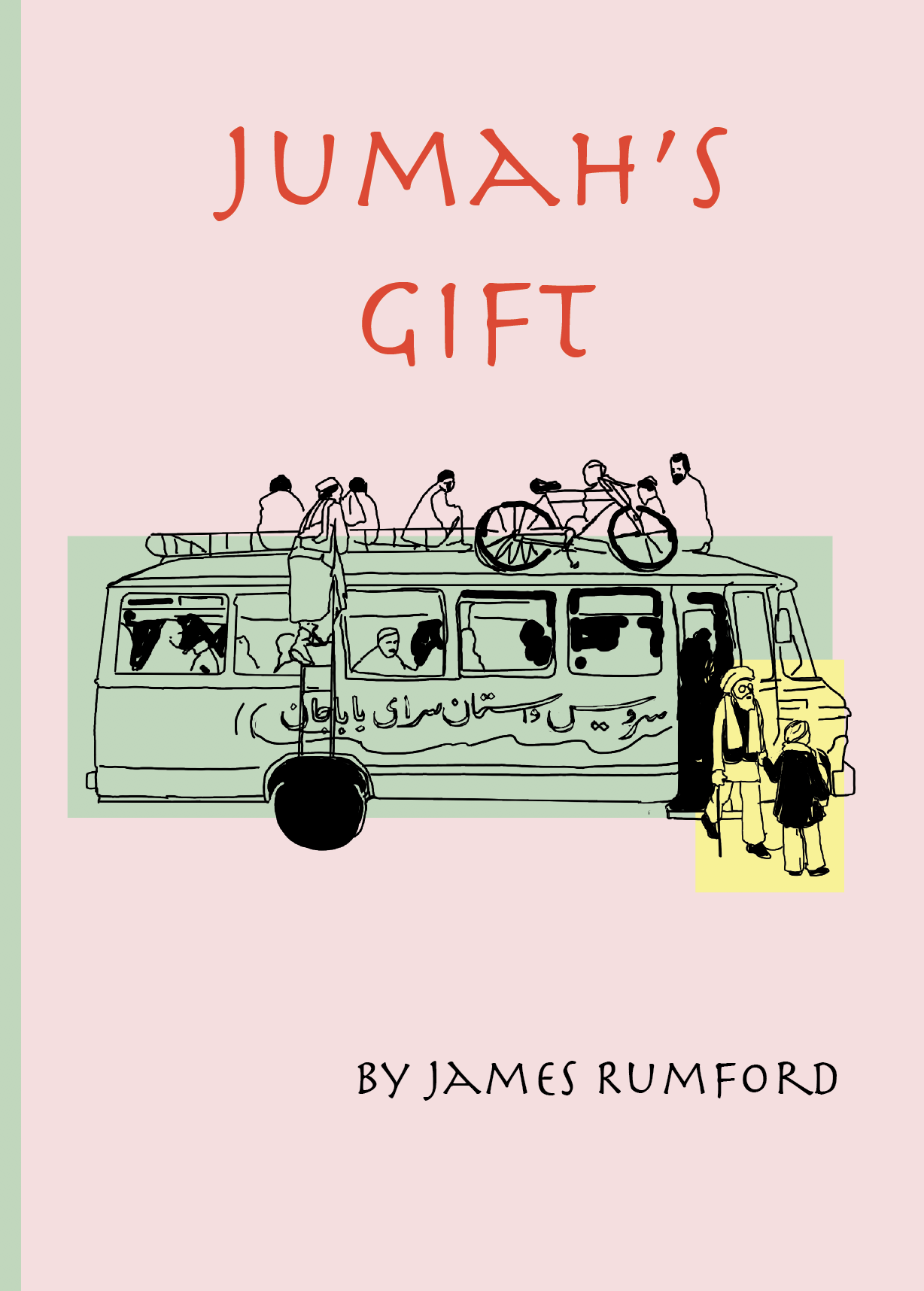

To purchase a copy of

Jumah's Gift,

click here.

This book began twenty years ago when I saw a Persian miniature of man leaning against a massive pillow reading. By his side was a pot of tea and a sleeping cat.

In my notebook, I jotted down these words and imagined the cat to be a monkey:

As I dipped my pen in the ink, monkey upset my cup of tea—leaves and all flowed out onto the carpet and made a blossom-like stain. “Monkey,” I said, “You’re a genius!”

And as I wrote those words, I imagined an entire book about a storyteller who got his inspiration from the designs and stains on his carpet. I saw how the original tales I would create could tell another story: about the relationship between an old storyteller named Baba-jan and an orphaned boy named Jumah.

In this way, Jumah’s Gift was born.

It is foremost a book about friendship through sacrifice. Second, but just as important, it is a story about the power of imagination. To return to the inspiration for this book, what may be just a tea stain to many could be in the mind of a storyteller and a ten-year-old boy a glimpse of another world where elephants have wings, noodles turn into vipers and flakes of red pepper will buy the hand of a sultan's daughter.

[an excerpt from the first chapter]

1 :: The DOOR

There was a door opening at the edge of Kabul. It wasn’t a real door, but it was like one, as a ten-year-old boy fresh from the war-torn countryside stepped onto the city streets, forced to begin a new life.

In ancient days, there would have been a real door—a gate really—and a high wall to greet the boy and welcome his arrival. But these were modern times. The gate, the high wall were long gone. No one was there to greet him. He saw only heads bent down in the cold wind and a city that stretched endlessly before him, a bombed-out city of broken walls and broken homes. Somewhere down one of these streets was a house that belonged to his aunt, a house where he had come with his father and mother just the summer before.

The boy stopped to get his bearings. He looked behind him to make sure those boys weren’t following him. Just a little while before they had hassled him. They had taken his cap and the bag, containing the only extra clothes he had, and they had demanded money, but he had no real money. Just a few paisa that he had wrapped up in his turban cloth. But they had found that and pushed him to the ground for lying to them. He clutched the cold dirt when they kicked him. Then they ran off.

But there was something in the dirt: a coin! A fortune to him now. He searched around for more, but there were no more coins. The boy stood up and dusted himself off. He didn’t know whether to think he was lucky or not. He had no money but this coin and more important, he didn’t know where he was. Under a blanket of snow, everything looked different, and fear every bit as sharp and cold as the wind, bit into him. He brushed his dark brown hair out of his eyes. What if he couldn’t find his aunt’s house? But he couldn’t think about the “what if’s,” just as he couldn’t think about what had happened that morning or the day before. He closed his mind to the past, stuck his freezing hands in the pockets of his red coat, now ripped in places from the boys, and went on.

“I’ll just take the main road,” the boy said to himself. “I’ll recognize something.”

When he passed a bakery painted pink and green, some memory from last summer told him to turn left and follow the winding streets. When he got to the mosque, he knew to turn right. Up ahead was the fruit seller’s where last summer a white cat had slept sprawled out in the shade. His aunt’s house was just around the corner.

The boy stopped in shock. The house was gone—nothing but rubble.

“What are you staring at, bacha?” asked a nervous woman on her way home.

“My aunt’s house,” said the boy.

“It was blown up— can’t you see?”

“Where is she now?”

“Gone...dead...who knows?”

The boy turned again to look at the rubble, the collapsed walls, the splintered gate. When he turned around, the awful woman was gone.

A crow atop the bombed out house cawed then disappeared into the coming night—like the woman.

For a long time the boy stood in front of the bombed out house until a gust of cold wind, like a slap, jolted him back to his senses. He could not stay there. He’d freeze to death.

On the way back to the main road, the boy thought about that crow and imagined that it was the woman. The boy laughed to himself, thinking of her cawing behind her veil and flapping her dark, chadri wings as she flew high above the rooftops.

When the boy reached the pink and green bakery on the main road, he went inside and bought a flat slab of hot bread with that afghani coin he had found. Even though the shop was tiny, the boy managed to find himself a small corner where he could eat. As more and more customers crowded in, the boy pressed himself against the wall unnoticed—unnoticed until the last loaf had been pulled out of the oven pit and the last customer gone home.

“Boy, what are you still doing here?”

“I...I....”The baker didn’t let him finish. He had seen a lot of terrible things in the past few months and knew a homeless boy when he saw one.

“All right. You can stay here the night, but be gone at white-dawn.”

The man seemed gruff, but later he brought hot soup.

Warm for the first time in days, the boy bunched up his coat for a pillow and fell asleep.

White-dawn, the first light of day, came soon enough, and when the boy awoke, the shop was again filled with customers. Beside him was a slab of bread and some cheese tied in a kerchief. There were so many people in the shop that the boy could barely see the baker, his cheeks flushed red from the hot oven. There was no way to thank him. The boy picked up the kerchief and made his way out.

The sky was getting lighter and the clouds were just turning pink from the rising sun—no, thought the boy, from the glow of a giant’s oven as he opened it to take out moon-sized cakes. And so the boy told himself a story about the giant baker in the sky, not just to amuse himself but perhaps to chase his fears away.

Clutching his kerchief of food, the boy took a deep breath and turned his attention to the main road now bustling with people. He stepped forward and disappeared into the crowd, hoping they were going to the center of town, where he had seen beggars the summer before. He would be one of them now.